Plan for Consolidating FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting Systems: Good Idea but Easier Said than Done

August 28, 2025

.jpg)

Commissioner Marty Makary announced an agency wide, comprehensive effort to consolidate disparate adverse event (AE) reporting databases as one of his first 100 days accomplishments. This is an idea that has been discussed for years but not prioritized due to resource needs and difficulty.

Makary has repeatedly pointed out the “clunky” adverse event reporting systems at FDA. Recently he stated in a CNBC interview, “We have one for vaccines called VAERS and one for devices called MAUDE. We have VAERS and KAERS and FAERS and Sentinel. We have 10 different adverse event reporting systems, all sort of independently developed. We’re going to go to one.” Although Makary does not identify which 10 reporting systems he plans to consolidate, his broad complaint is against the fragmented complex of passive and active national surveillance systems, which tend to be divided by product type, combined with state-level systems and hospital/institutional tracking tools.

We applaud the Commissioner for launching bold new initiatives that potentially offer greater safety (and hopefully benefit) insights. However, we would suggest having a more public and transparent conversation around what consolidating the systems would accomplish and what is most needed to enable more effective and efficient post-market safety monitoring.

Why are there so many AE tracking systems?

The diversity of FDA adverse event reporting systems is based on the fact that each was purpose-built for different products, stakeholders, and statutory requirements established by law over decades. These systems were built at different times (some in the 1990s, others in the 2000s or later), using different data models, technology stacks, and available computing tools at the time. They weren’t originally designed to interoperate; instead, each evolved organically for its own mission.

Of note, each system serves different user groups (i.e., manufacturers, healthcare providers, consumers, and regulators) who have unique needs and expectations. For example, the FDA's various centers and offices have developed distinct adverse event reporting systems tailored to their specific regulatory needs for the three passive national reporting systems: VAERS (the Vaccine AE Reporting System), MAUDE (Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience), and FAERS (the FDA AE Reporting System) for drugs and biologics.

While the FDA’s fragmented post-market safety infrastructure can seem outdated or redundant, much of that fragmentation is the product of distinct statutory requirements and limited budget flexibility.

Potential Benefits of Consolidation

Consolidating FDA’s three primary, passive adverse event reporting systems could offer several meaningful benefits, both for the public and for regulators seeking to modernize safety surveillance:

- Operational Efficiency: Shared infrastructure could reduce redundancies and lower administrative overhead over time. This is especially relevant to the FDA’s recent push towards higher efficiency.

- Improved Data Accessibility: Combining systems could facilitate more comprehensive data analysis and safety signal detection across product types. This could also enable safety researchers to identify patterns or interactions across different product categories (e.g., drugs and devices used together).

- Enhanced Data Mining & AI Capabilities: Unified data architecture could enable more robust real-time safety surveillance using machine learning and AI tools, which the FDA has been expanding recently.

- Increased public Transparency & Trust: A centralized platform might improve public confidence by making safety data easier to access, compare, and interpret. A push for transparency has been stated to be at the forefront of Makary’s proposed vision for the agency.

- The potential for increased awareness for how and where to report: The process of combining the three systems could be an opportunity to raise awareness of the existing joint portal for voluntary and mandatory entities to report AEs for all three databases—MedWatch.

Debate continues over the intrinsic value of passive versus active surveillance in safety monitoring. We may explore this in greater depth in a future blog post, but in brief: proponents of active systems (e.g., FDA’s Sentinel Initiative and its BEST program) argue they can mitigate common shortcomings of passive reporting, including underreporting and delays. While these potential benefits present a compelling case for expanding active surveillance, moving toward a single, integrated system will require overcoming significant legal, structural, and technical hurdles.

Regulatory Drivers Behind System Fragmentation

The FDA did not create multiple AE systems arbitrarily. Rather, the agency implemented different Congressionally required activities and met the reporting obligations created by various regulations:

- 21 CFR Part 314.80 governs drug safety reporting for FAERS.

- 21 CFR Part 803 mandates device reporting requirements that structure MAUDE.

- VAERS operates under the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (NCVIA) of 1986, which uniquely requires co-management with the CDC and supports the federal vaccine injury compensation program.

Each statute prescribes distinct data elements, timelines, and submission formats. As a result, the systems were never built to be interoperable. See the table provided below comparing the systems’ current structures. Unifying them would require Congress to amend multiple federal laws, including the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act); the Safe Medical Devices Act; and the NCVIA.

Hurdles for Combining Systems:

Statutory:

- A full merger would likely require major statutory changes and a fundamental redesign of FDA’s surveillance processes, something that has high costs and risks alongside potential benefits.

Technical:

- Combining them would be challenging due to incompatible data structures, different legal mandates and specialized workflows.

Procedural:

- Some consolidations will require interagency agreements as well.

Resources:

- Even if statutory hurdles are removed, funding could be a challenge, especially within the current federal budget environment which is focused on decreasing spending. Congress allocates funds to the FDA by product center, limiting the agency's flexibility to fund unified infrastructure projects like an overarching adverse event reporting system.

- An alternative funding source could be negotiated under the multiple user fee efforts like PDUFA (drugs), BsUFA (biosimilars), MDUFA (devices), and GDUFA (generics), however each of these negotiated fees restrict tend to target money to their respective centers and activities. FDA cannot legally redirect user fee funds to build cross-cutting infrastructure for MAUDE or VAERS, without this being part of the upcoming negotiations.

- Additionally, the Office of the Commissioner could allocate its funds for this project, but would first need to identify a source. If the funding falls outside the amounts already appropriated by Congress to the FDA, securing it would require navigating the lengthy and complex appropriations process.

In short, integrating systems could require new congressional appropriations language with a cross-cutting IT infrastructure budget line and user fee reauthorization with shared infrastructure carve-outs. Creating an integrated AE system would require new appropriations language or user fee reauthorization bills with explicit carve-outs for shared systems.

Legacy Technology

Even with legal authority and funding, there will be technical challenges to integration. Each system runs on different technical standards:

- FAERS uses the ICH E2B(R3) standard;

- MAUDE relies on HL7 ICSR and older proprietary formats; and

- VAERS has a unique data structure tailored to CDC collaboration and injury compensation.

Integration would mean decommissioning current systems/databases, aligning data standards, and retraining staff across multiple FDA centers. Meanwhile, VAERS data also supports CDC's Vaccine Safety Datalink, which raises additional legal and interagency governance issues. Existing interagency data-sharing agreements may require renegotiation.

So, with an integration goal, what are potential first steps?

Since we know the new Administration likes to use AI tools, we decided to ask ChatGPT on what first steps for consolidation might be the easiest to achieve in the near term. Here are a few ideas:

Note: Many of these have not been included in the post in order to keep it brief. Additionally, they are outside the scope of drugs, biologics, and devices.

Our view of low hanging fruit: focus attention on Sentinel, including BEST

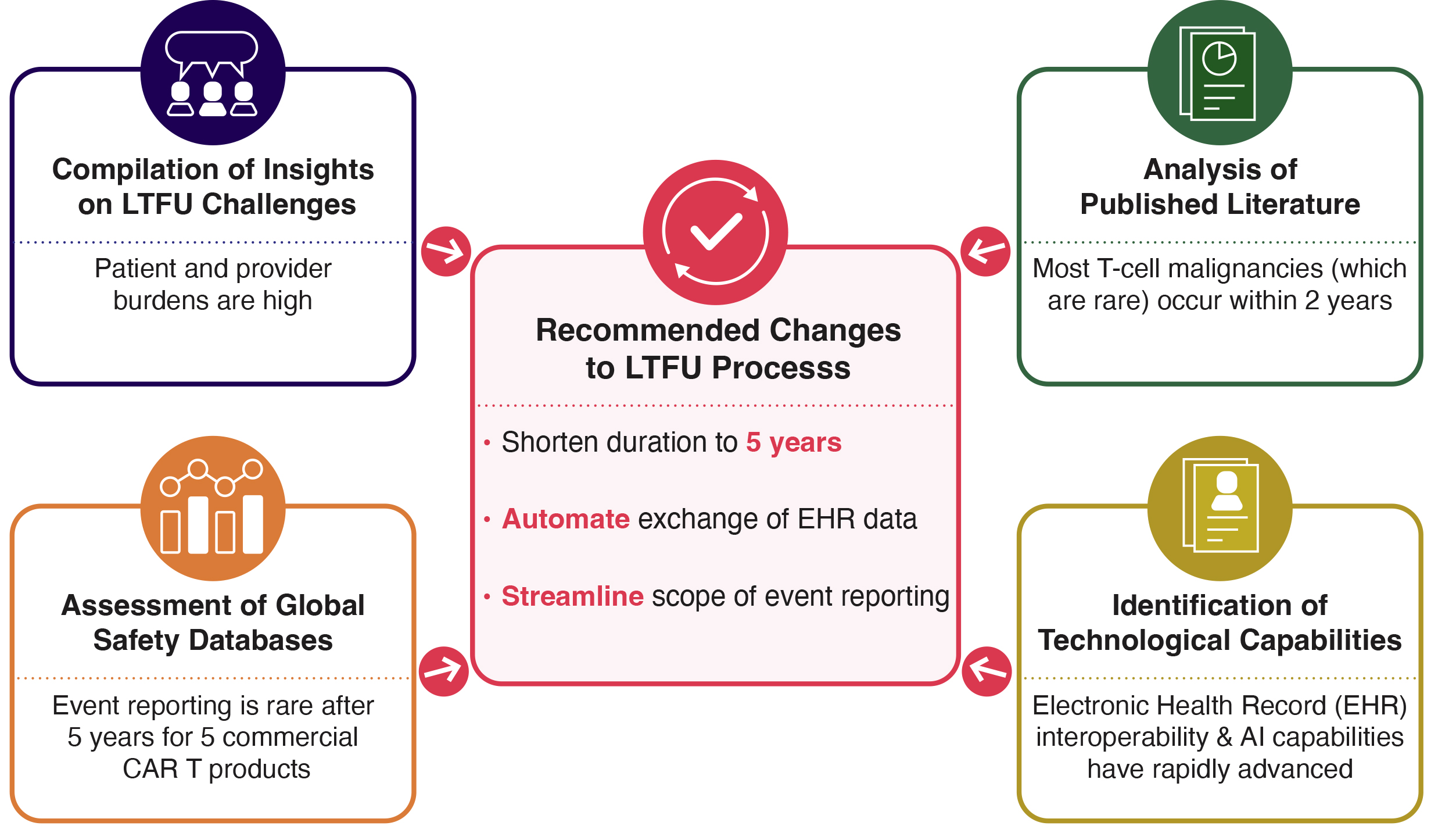

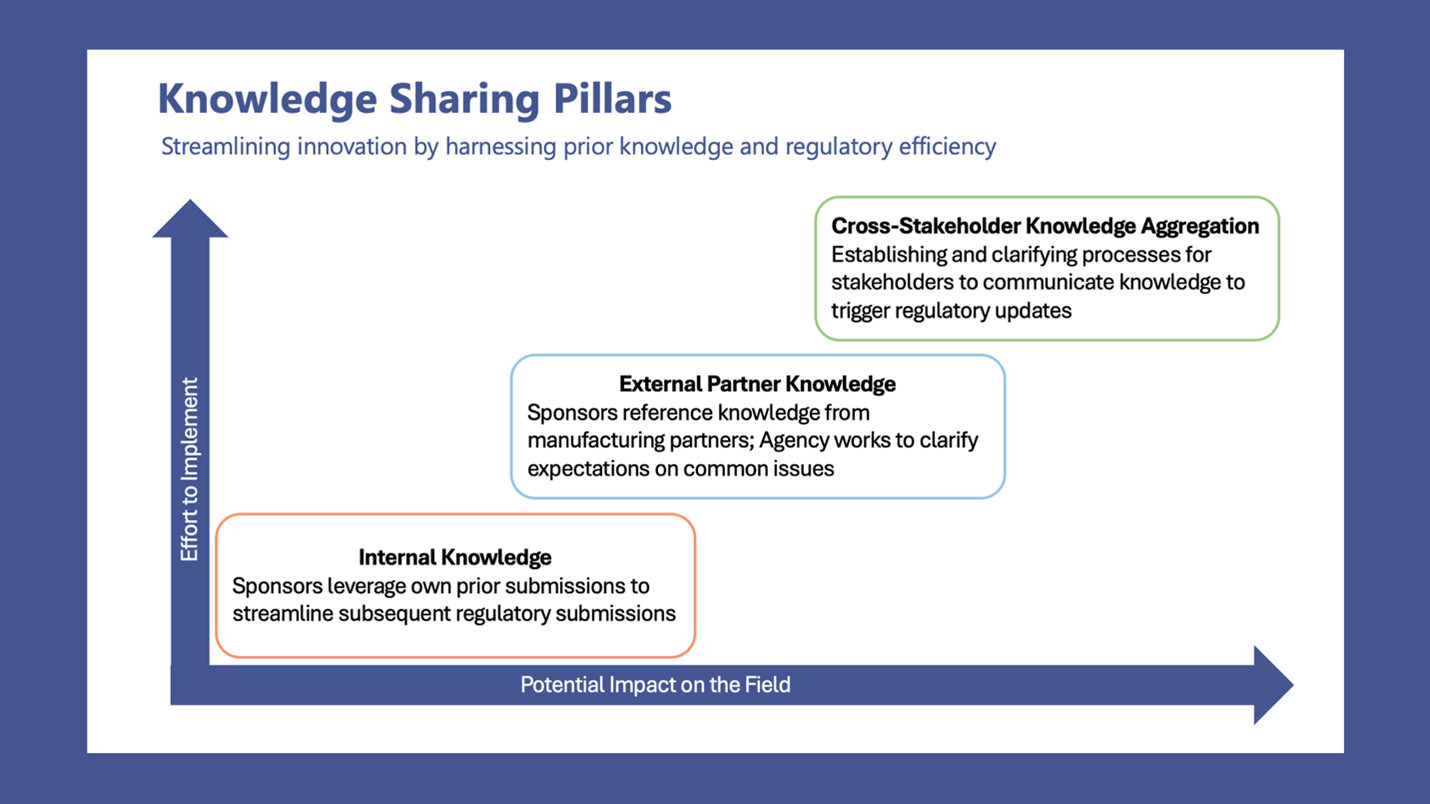

In an FDA Direct podcast, Makary emphasized the limitations of current self-reporting systems. He explained that combining these with real-world data from claims and EHR platforms would dramatically improve speed and accuracy of safety signal detection. It would also help completeness. Whether the established systems are fully consolidated or not, the use of RWD would address many of the problems of the current process of passive reporting. Sentinel and BEST are the agency’s core active safety surveillance programs that use real-world data (RWD) to monitor the safety of regulated products. Makary has only briefly referenced Sentinel in his public discussions on FDA's adverse event (AE) reporting systems. FDA’s efforts to modernize its "clunky" AE reporting systems should first involve building upon these programs as a constructive and forward-looking strategy. While expanding these systems will require resources on the front end, the ability to automate the collection of AEs from EHRs could, in time, decrease or eliminate the need for passive reporting, and save time and effort for patients, healthcare providers, manufacturers, and the FDA in processing current manufacturer-required reports on long-term safety.

While there is more work to be done to expand the capabilities of these systems, recent advances in interoperability (e.g., AI) signal that the time is right to move toward these active systems that have automated data transfer potential.

Final Thoughts

Dr. Makary has touched on a real area of potential improvement for the Agency: the FDA’s adverse event reporting systems are disjointed and could benefit from a new technology lens. However, significant hurdles remain, including obtaining congressional approval, navigating interagency coordination, and implementing stakeholder input. Greater transparency is needed, both on what will be included in any system consolidation and how the consolidated system will be implemented and used. We will continue to closely monitor this effort.